I am continually surprised by the degree of innovation and world class engineering successes of Canada during the 1950s through to the 1960s for military and aerospace hardware. Domestic spending priorities and the cessation of the Cold War gravely reduced defence spending and the spelled the end of this period although civilian commercial aerospace is still a strong industry in Canada. Frequent readers will be familiar with the relevant topics visited earlier in this blog.

During the height of the Cold War, the US was intent on developing Vertical/Short Take Off and Landing (V/STOL) aircraft given that a first strike doctrine by the enemy would be to target all airfields in North America and deny us a counter strike capability. These aircraft would allow us to maintain air superiority by operating from roads, shortened runway or unprepared areas. Fortunately, this scenario never manifested and as a result the US never fully adopted a V/STOL aircraft for many decades until the Boeing Bell V22 Osprey became part of the US Marines in the 2010s (I’ll discount the Harrier II that the US Marines also used because it is a specialized attack aircraft not meant for a multirole mission).

Canadair today is known for its highly successful Challenger 600 business jet which is still in production after four decades and with over a thousand built. Canadair (Montreal) was originally the aircraft division of Canadian Vickers Ltd, a crown corporation. It was sold to the Electric Boat Company in 1947 which became known as General Dynamics in 1952. Canadair was Canada’s largest manufacturer of aircraft best known for its most refined and powerful variant of the F-86 Sabre fighter jet of the Korean War and CL-215/415 water bombers. Canada reacquired Canadair in 1976 and it was then bought by Bombardier in 1986.

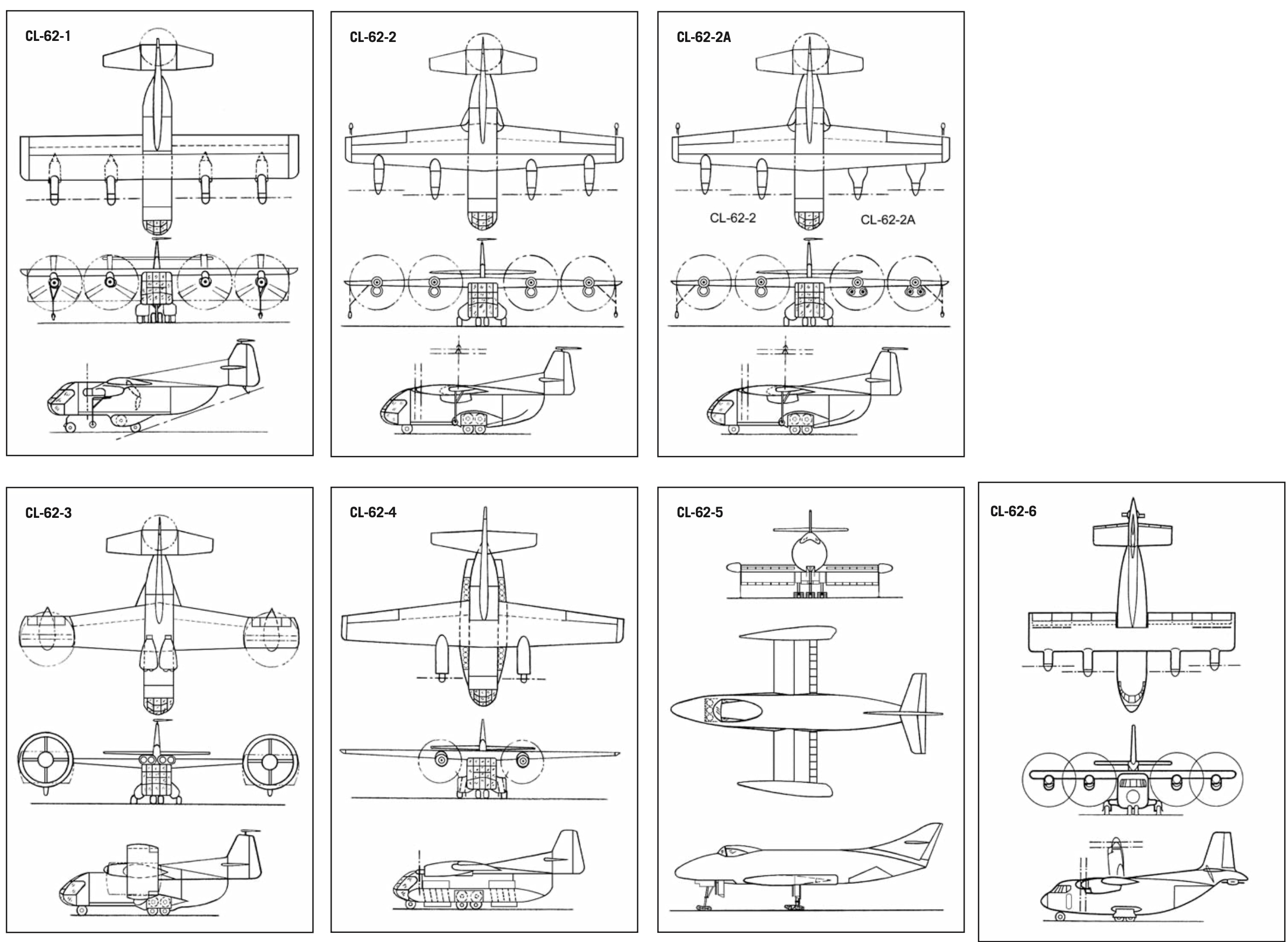

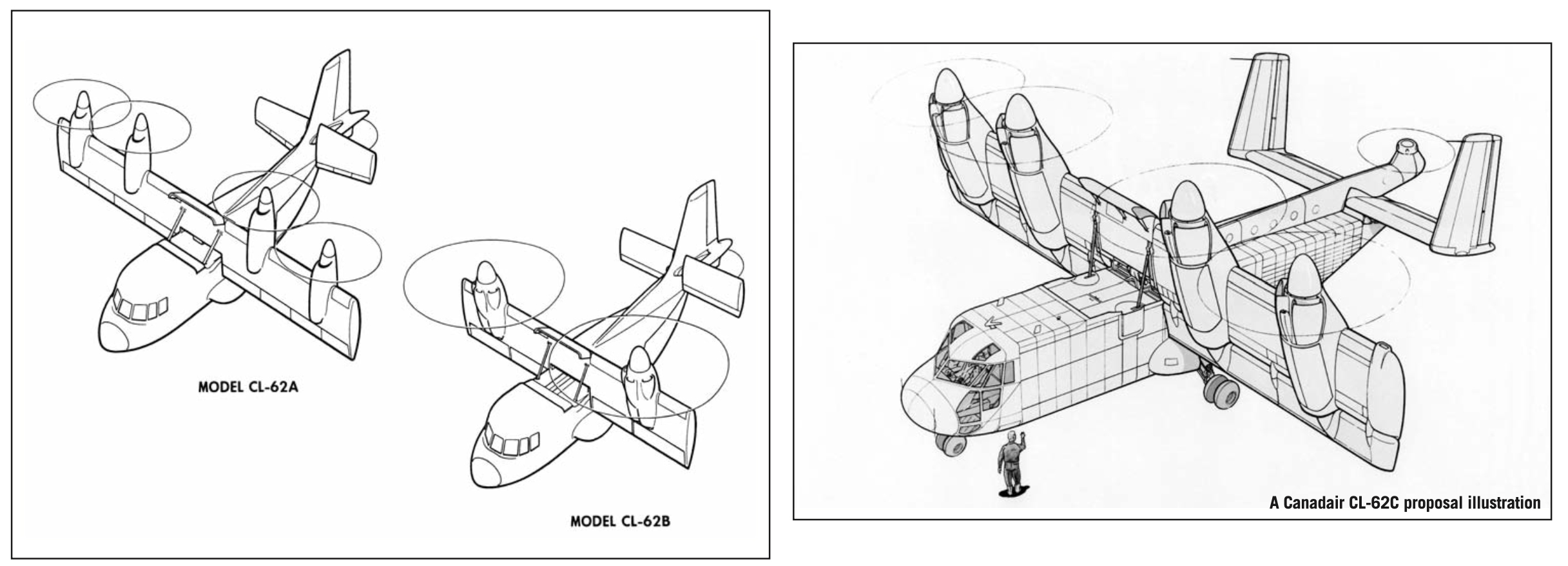

Canadair experimented with three V/STOL designs using wind tunnel testing at the National Research Council (NRC): (a) tilt wing/slipstream deflection, (b) tilt engine and (c) fan in wing¹. A decision was made to concentrate on design (a) as the most promising approach.

¹ the thrust producing fan is horizontally embedded in the structure of the wing driven either by shafts from a gas turbine or even by compressed air jets at the blade tips provided by a turbine driven radial air compressor.

In August 1963, the Department of Defence Production contributed the lion’s share of the $10 million budget to design and build a flying prototype of the CL-84. One can easily imagine the many technologies that needed to be invented at Canadair to solve the multitude of problems with actually constructing a flying tilt wing V/STOL. Engine, oil and fuel delivery systems had to function in both horizontal and vertical orientations. The mechanism to tilt the wing. The complex shaft linkages between both turbine engines so that one engine failure would still allow the remaining engine to power both propellers. Perhaps the most innovative feature was the development of a mixing box which allowed the pilot to always fly the controls in the same manner with the box automatically making the flight corrections needed (through a series of six linked cams and levers) depending on the flight orientation. Pilots did not need to learn how to fly the CL-84. To bank the CL-84 you move the flight column to one side to engage the ailerons, but in vertical flight the same movement causes the mixing box to vary the blade angle of the propellers. A turn is made by pressing the foot pedals to turn the rudder, in vertical flight the ailerons are deflected. A climb or dive is initiated with elevator movement but in vertical flight the variation in tail rotor thrust controls that movement. A conventional throttle lever controlled engine power with a top mounted thumb switch controlled wing tilt, pushing it aft raised the wing.

FIrst flight occurred on May 7th, 1965 involving only vertical maneovers. Conventional flight took place on December 6th and the first transition from and to hover on January 16, 1966. In September, five outside pilots were invited to fly the CL-84, from the RCAF, RAF and NASA. Later seven other US military pilots flew it for a total of 21 hours and enthused about its easy flying experience. A year later, on September 12th, 1967 the CL-84 prototype was flying its 306th flight with a total of 145 flight hours and 405 operating hours when an off the shelf bearing failed in the propeller speed control mechanism and the plane yawed hard left and pitched nose down. Both crew members safely ejected before it crashed and burned.

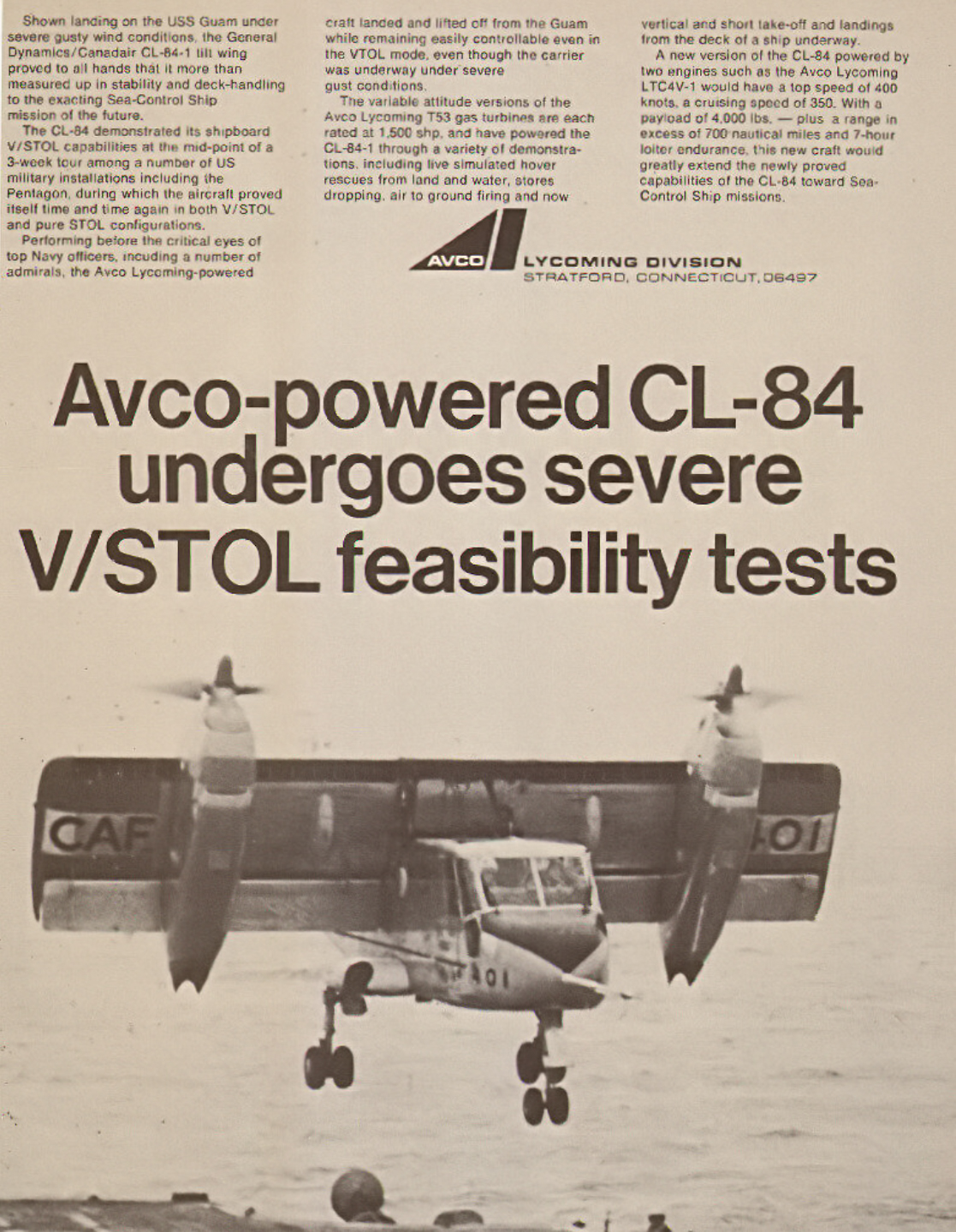

The Canadian federal government purchased three new model CL-84-1/CX-84 aircraft at an initial cost of $13.1 million in July 1967 for evaluation by the Canadian Armed Forces. Over 150 modifications were implemented in the new design reflecting feedback from the diverse group of pilots which had flown the prototype. The fuselage was extended 5 ft with bench seating for 12 passengers, more powerful 1800 bhp Lycoming engines were used. Three under fuselage hardpoints were introduced as well as two outer hardpoints for jettisonable fuel tanks. The first CX-84 was flown on February 19, 1970.

The CX-84 project died when no foreign orders arose from interested countries such as Germany, Holland, Italy, the UK, Sweden, or the US. To be fair, the Canadian Armed Forces themselves decided to go with Bell CUH-1H Iroquois helicopters so it was unlikely that other countries would be swayed by a Canadian rejection of its very own. And as was explored in an earlier blog entry concerning the ill fated Avro Arrow, the US is typically unlikely to purchase complete foreign military products for political reasons and the cost overruns of the ending Vietnam War also made such purchases highly unlikely. Lessons learned with the CX-84 influenced the design of the V-22 Osprey but even that modern aircraft still lacks some of the capabilities of the CX-84. The STOL takeoff performance of the CX-84 is far superior as well as much shorter transition time from hover to conventional flight and a demonstrated maximum airspeed of 345 mph (555 km/h). The two surviving examples can be found in aerospace museums in Ottawa and Winnipeg.

I do not know the glide ratio of the Canadian planes but the Osprey’s glide ratio is pretty much indistinguishable from a brick. That’s the problem.

“We create our fate every day . . . most of the ills we suffer from are directly traceable to our own behavior.”

Sent with Proton Mail secure email.

LikeLike

Excellent article, especially accurate regarding the mixing box role in very favorable pilot acceptance. Nowadays the function is implemented in fly by software controls, the Marine F-35 forward somersault being a good example.

As a very junior engineer in the Canadair simulation lab I reprogrammed the simulator to include a digital computer for the complicated aero coefficients and to provide a simple but useful visual display. In the course of doing that I accumulated about 500 hours of “flight” time. It was indeed easy to fly.

The CL-84 was an engineering success but unfortunately a marketing failure.

LikeLiked by 1 person