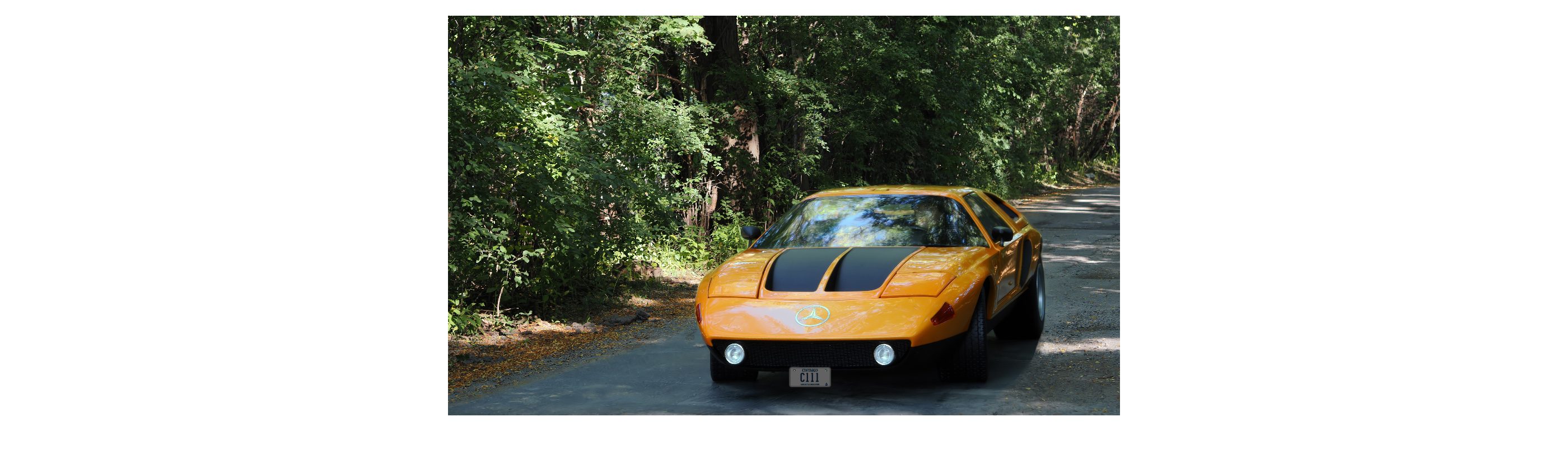

It’s not surprising that the premiere unveiling of the Mercedes Benz C111 with a mocked up three rotor Wankel engine in September 1969 was greeted by blank cheques offered by prospective buyers. The company has yet to produce a more stunning prototype model. (the title image was again shot in forced perspective with a 1:18 scale model)

Despite issuing 23 licences for the manufacturing of the Wankel engine by NSU to multiple car and engineering firms, clearly the excitement of the design had blinded everyone to the consideration of the development costs, which would prove to be astronomical. Even though Daimler Benz was an earlier adopter by 1961, they were not true believers and to them the Wankel engine was not a matter of survival, as it was at Mazda.

The principal issues with rotary engine development were cooling, gas sealing of the combustion chambers and whether exhaust gas should exit ports on the periphery of the housing or through the side housings themselves.

After two years of development, the first engine was a 1.4L twin rotor producing an astonishing 170 bhp but suffered terribly from temperature related apex seal failures and the destructive wear formation known universally as chatter marks. Reducing output to 145 bhp allowed it to survive 400 hrs of bench testing. At the end of the next year (1963) a three rotor producing 210 bhp was developed but when limited to only 141 bhp was installed in a W111 sedan in 1965 and produced significant exhaust smoke and oil consumption of some 4 L/1000 km. Refinements continued but real world fuel consumption was still high, alarmingly high even for the world of the 1960s.

But the uncompromising quality standards at Daimler Benz meant that they would never introduce a car like the excellent NSU Ro80 with a rotary engine that fatally compromised it. Passing thousands of bench and road hours was not enough. Too frequent spark plug changes, embarrassing exhaust fumes, and high fuel and oil consumption still plagued the experience. And the new environmental emissions regulations in the US would require the use of a catalytic converter.

By now it was clear that the rotary would be unable to replace any of Benz’s reciprocating piston engines. The only saving grace in the project was the potential cost savings associated with the far lower number of rotary engine components and the modularity they automatically supported in building increasingly more powerful engines (by adding extra rotors). But continued R&D expenses were required to produce optimized apex seals, eccentric bearings, rotors, and internal housing coatings. After spending 100 million deutsche marks (DM) and a decade and a half of work, no rotary engine made it to production but this amounted to only 3% of the company’s total expenditure over this period – such is the behemoth that is Daimler Benz.

In 1968, there was the sudden revival of midengined sports car referred to as C101 with visions of a homologated road vehicle using a 3 rotor, 300 bhp engine and a race version using a four rotor engine with 400 bhp. The project rapidly progressed through the full scale plasticine model and with the first ever use of computer aided design the structure was designed and manufactured as a complete rolling chassis. The first track test occurred in April 1969 with a 258 bhp 3 rotor engine, 0-100km/h was 5.8s and top speed reached at 230 kph with fuel consumption at 29L/100km.

Project C101 had been known by the public since the spring of 1969 and the news that Daimler Benz was building a Wankel powered sports car made the pending NSU merger with Audi even more attractive to NSU shareholders whose shares were bound to rise. But the board was more circumspect. The rotary engine failures meant that the question was no longer whether it should be used in principle, but in which application. The presentation of the C101 would have to be a targeted media release emphasizing it as a special model with no consequences for the rest of their conventional line of passenger cars in order to quell sensationalized reporting by trade magazines of the day. However the internal C101 designation had to be changed in light of a conflict with Peugeot’s naming tradition, which also flummoxed Porsche when it came to naming their new flat-6 901 model. The C111 was thus born.

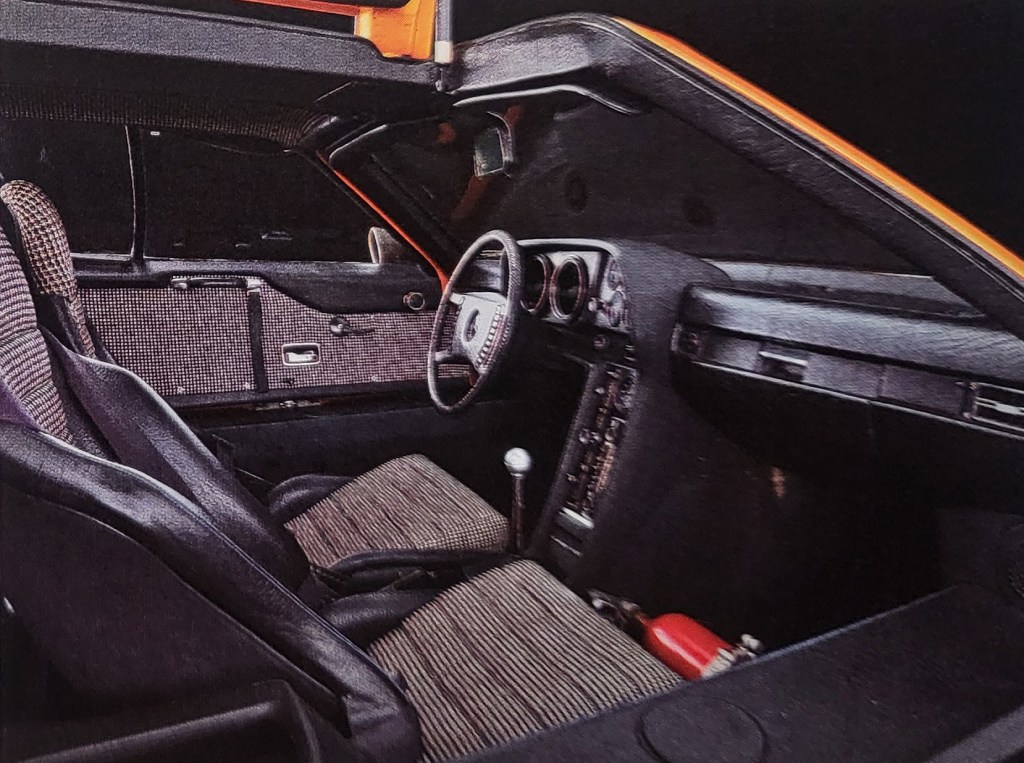

During the first week of September, cars 2, 3 & 4 were made available to the press core but they were only allowed to ride in them, not personally drive them. During these demonstration runs at the Hockenheim, the three cars covered a little under 2000 km but fuel consumption was nearly an incredible 40 L/100 km (that’s 6 MPG) and oil consumption 3-6L/1000km. Former F1 driver and journalist Paul Frère (who later become well known to North Americans as the enduring European Editor of Road & Track) had a chance to drive car 4 by himself. He described being shocked by the “ungainly monstrosity with a rear end brutally cut off” but when driving it his impression completely changed. He lauded the unimaginably smooth running Wankel whose exhaust note was so thoroughly muffled that only the dials informed him that he had once again exceeded the 7000 rpm limit. The low center of gravity, the balanced weight distribution of the midengine placement and the race suspension meant that he could enter each corner faster and faster and never found the limit during his test drive.

Car 6 was equipped with the 4 rotor engine rated at 367 bhp at 7000 rpm but the unusually high exhaust temperatures characteristic of a rotary engine destroyed the glass fibre sound deadening material in the mufflers and the car was loud! The car lapped Hockenheim at 2:10 with a maximum speed of 273 km/h while still accelerating but after only three laps the oil temperatures rose to dangerous levels and testing stopped. Despite an all fibreglass body, good aerodynamics and the relatively lightweight engine, performance was still not quite equal to that of its contemporary, the Lamborghini Muira. Car 6 ultimately did record a maximum speed of 297 km/h with some intake and exhaust tweaks, and 299 km/h with the sideview mirrors removed while travelling on a straight section of the motorway at 4 AM!

By the summer of 1970, it was decided that a new model, the CIII-2, was needed. Windows size and shapes were changed to improve rear visibility for the driver, the beltline was lowered, the aerodynamics refined to improve ventilation of the engine bay with the hot air exiting the negative pressure region generated at high speed at the nose of the hood outlined by the new twin sculpted black scallops. The response to the board’s feasibility study for a limited production of C111s was that if 50 units were manufactured, the asking price would be 75,000 DM which would be about 3x the price of a Porsche 911. This price would fall to 42,000 DM if a 1000 unit run was considered but still expensive. With that, the board decided to terminate the project and allow the existing prototypes to showcase the exciting future while giving the public a behind the scenes look at product development at Daimler Benz. (what remains unsaid is that the Benz rotary engine was not anywhere ready for prime time notwithstanding the stringent quality requirements of the company).